My dad passed away 14 years ago this week. About a decade before that, he suffered a stroke that slowed him physically but didn’t stop the way he drew insights (although it did remove some of his filters which produced some surprisingly humorous outcomes). His spark was still there. He had a way of pulling together threads no one else thought to connect, and even after the stroke, he could cut through complexity with a clarity that made you stop and rethink your positions.

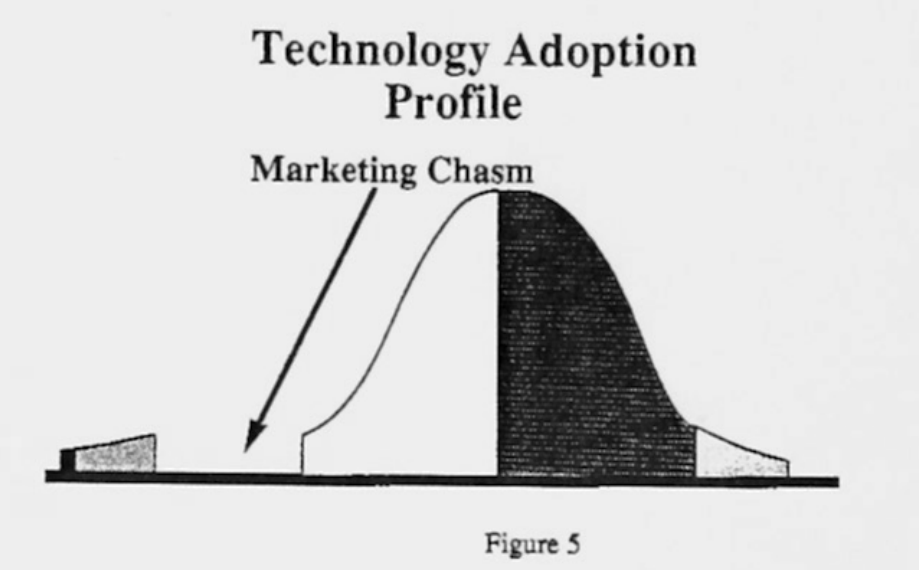

He was one of the creators of the original concept of “crossing the chasm” — the framework Geoffrey Moore later popularized in his book (original product here and here – I continue to appreciate Warren Schirtzinger’s passion around maintaining that history). The idea that technology adoption moves differently, that those products that have the greatest early success tend to stall out before going mainstream, was theirs. That kind of insight wasn’t born from reading one market report or trend piece. It came from years of seeing patterns where others saw noise, of spotting trajectories when everyone else was focused on the present moment.

That was my dad’s gift: perspective based on deep experience and wisdom from a history of seeing trends in the static where most just saw what was right in front of them. He could look across disciplines — business, politics, technology, science, human behavior — and connect dots that seemed unrelated until he put them together. It wasn’t just foresight; It was synthesis. He was the ultimate example of David’s Epstein’s Range which may explain why it is one of my favorite books.

Today, in the middle of the AI revolution, I can’t help but think how much the world could use his mind. We’re in a moment where the pace of change is faster than our ability to interpret it. Every week brings new breakthroughs, new promises, new anxieties. There’s an event horizon that most of us can’t see over that has shrunk from decades to years to quarters and now to months as the pace of change accelerates. Models can summarize, remix, and predict, but they can’t provide meaning. They can’t tell us what matters, what’s durable, what’s just noise.

That requires humans who have the scar tissue of experience, who have lived through cycles of hype and disillusionment, who can see not just the product demo in front of them but the trajectory it suggests. My dad was one of those people. And if he were here today, I know he would have a great perspective — and would provide it to me and anyone who would listen — to make sense of what AI means beyond the headlines.

So yes, I miss him because he was my dad. I miss his humor, his encouragement, his presence. But I also miss him for what the world could use right now: a steady voice of perspective in the middle of chaos, a connector of dots when the picture feels fragmented, someone who could see beyond the event horizon and help us chart a course.

In an age where AI is amplifying everything — both the noise and the signal — the ability to find clarity has never been more valuable. That was his superpower; I really miss him.